Part Two: Differences

Part One, "Down, Down to Goblin Town" explored some of the similarities in the Goblin race between J.R.R. Tolkien and George MacDonald. You can find it here.

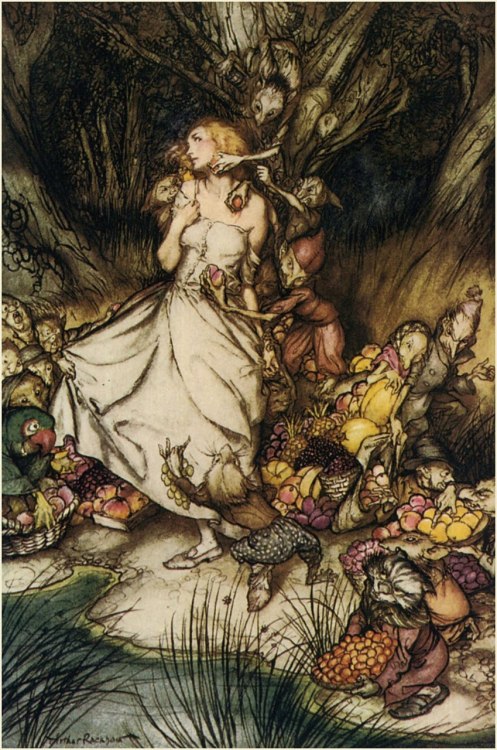

While there are some similarities between the goblin races represented by Tolkien and MacDonald, there are many more differences. For instance, in keeping with somewhat typical Tolkien fashion, there is never any mention of a

female goblin in

The Hobbit. They certainly exist, for how else would Gollum be able to capture a "small goblin-imp" (128)? But, as John Rateliff states in

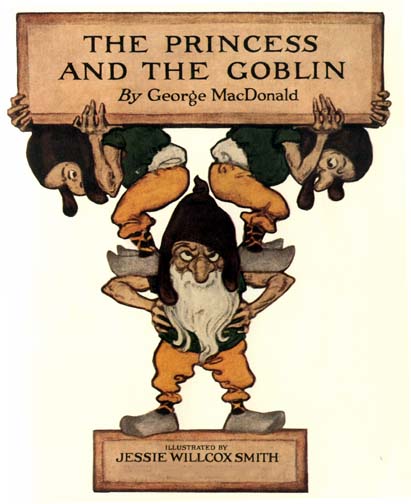

The History of The Hobbit, "there is nothing in Tolkien's story to parallel MacDonald's indomitable goblin queen, who stomps on her enemies' feet with her great stone shoes"(140). Which brings us to one of the more obvious differences between goblin races: in

Princess and the Goblin, the goblins have sensitive feet.

Extremely sensitive feet. The goblin queen's stone shoes protect her natural weakness, but also serve as a pretty effective weapon against those who would disagree with her.

Tolkien admits that he "never believed in"(141) MacDonald's idea of soft goblin feet. And, though the image of a secret, vulnerable soft spot slightly recalls Tolkien's Smaug, it's something that is absent in his Goblins. Tolkien might have disliked how MacDonald's goblins, who are a malicious and intelligent society able to plan a nearly successful attack on the royal castle, are made almost comically vulnerable by their soft feet. One shout from Curdie during battle and the goblins are bumbling fools, painfully exposed and defeated:

"'Stamp on their feet!' he cried as each man rose, and in a few minutes the hall was nearly empty, the goblins running from it as fast as they could, howling and shrieking and limping, and cowering every now and then as they ran to cuddle their wounded feet in their hands..." (208).

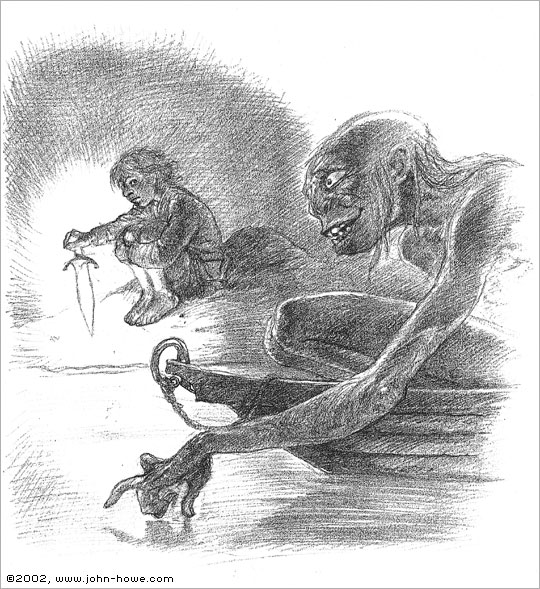

The last major difference is probably the most complex and interesting one. This, of course, concerns goblin song and singing. In chapter 4 and 6 of

The Hobbit the goblins sing not one, but two different songs. The first one begins:

Clap! Snap! the black crack!

Grip, grab! Pinch, nab!

And down down to Goblin-town

You go, my lad!

Tolkien scholar Corey Olsen does a lot of analysis of Tolkien's songs in his new book,

Exploring J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit. He does a wonderful job pointing out that the songs in

The Hobbit reveal a lot about the person or race who is singing it. The goblin song, he states, is "simplistic and blunt" but instead of telling us the goblins are unintelligent and unsophisticated, "the monosyllables that they choose are mostly onomatopoetic...the result is a verse that would sound harsh, ugly, and cruel even if we didn't know what the words meant" (75).

The goblin songs in

The Hobbit are not especially eloquent or sophisticated, but they are songs nonetheless. They are a

sort of art form, expressing their love for what they do, even if its a nasty and repulsive thing (Olsen, 77). Their first song shows just how much they will enjoy the "swish, smack!" of their "Whip crack!"

The goblin songs -whether intentional or not- are also a tool, a weapon for intimidation and fear. They sing their second song as a sort of taunt to a frightened Bilbo and company, who have all climbed up trees in effort to escape the goblins:

"Smoke was in Bilbo's eyes, he could feel the heat of the flames; and through the reek he could see the goblins dancing round and round in a circle...he could hear the goblins beginning a horrible song:

Fifteen birds in five fir-trees,

their feathers were fanned in a fiery breeze!

But, funny little birds, they had no wings!

O what shall we do with the funny little things?

Roast 'em alive, or stew them in a pot;

fry them, boil them and eat them hot?

Then they stopped and shouted out: 'Fly away little birds!...Sing, sing, little birds! Why don't you sing?" (151)

Bilbo is in a horrible situation, but the goblin's song and dance make it a terrifyingly eerie one. The goblin's song continues to show the morbid joy they'll find in killing the dwarves. But their song is weapon of fear just as much as it is of their own personal enjoyment. They do not mean to cook or "roast" the dwarves, but they sing of cooking the dwarves as a "cruel mockery"(Olsen, 118). They are striking fear into the company and relishing it. Their taunt of "Why don't you sing?" is of course, an invitation for Bilbo and the dwarves to scream in pain.

This is the type of singing Tolkien's goblins revel in- a painful, tortuous singing that only they could enjoy.

MacDonald's goblins couldn't be more different in this regard. It's not just that the goblins in The Princess and the Goblin don't sing. Singing is actually - perhaps even more so than their sensitive feet- their ultimate and clearest weakness. The narrator tells us, "They can't bear singing, and they can't stand that song. They can't sing themselves, for they have no more voice than a crow; and they don't like other people to sing" (36). But there's more to it. Curdie explains, "If [anyone] gets frightened, misses a word, or says a wrong one, they-oh! they don't give it to them" (37). It's not just the song that wards off goblins, it's the ineffable mixture of artistry and joy. Curdie does not fear the goblins and his songs show it:

"Hush! scush! Scurry!

There you go in a hurry!

Gobble gobble!goblin!

There you go a wobblin';

Hobble, hobble, hobblin;!

Cobble cobble! cobblin'!

Hob-bob-goblin!-Huuuuh!" (43)

Interestingly, Curdie's songs sound a lot like the goblin's songs in The Hobbit. While some are more complex than others, most are simplistic in rhyme and meter. The crucial difference is their content. Tolkien's goblins sing of fear and destruction, twisting it into a cruel joy. Curdie sings of joy in the face of fear: "We're the merry miner-boys, Make the goblins hold their noise!"

But Curdie has more complex songs as well. The most interesting one is easily:

'Once there was a goblin

'Once there was a goblin

Living in a hole;

Busy he was cobblin'

A shoe without a sole.

'By came a birdie:

"Goblin, what do you do?"

"Cobble at a sturdie

Upper leather shoe."

'"What's the good o' that, Sir?"

Said the little bird.

"Why it's very Pat, Sir -

Plain without a word.

'"Where 'tis all a hill, Sir,

Never can be holes:

Why should their shoes have soles, Sir,

When they've got no souls?" (142)

Again, like the goblins in

The Hobbit, Curdie sings of a "little bird", but the bird is not a representation of torture and pain. It's the voice of both reason and spirit, pointing out the futility of a goblin making a shoe without a sole (soul).

In

On Fairy Stories, Tolkien asserts that though finding writers' "sources" could be an interesting point of study, at some point, we all must enjoy the soup before us. There's a lot to see when we compare Tolkien and MacDonald, but in the end, both are a wonderful soup.

A little more...

*As a college student Tolkien wrote a poem called "Goblin Feet". He later grew to really dislike it. You can read it

here. Make what you will of the goblin's 'happy little', 'magic', 'padding' feet. :)

*The 1977 Rankin Bass

Hobbit film has a good amount of Tolkien's original songs in it. You can hear the editions of the goblin songs

here and

here. You can also watch an animated Curdie warding off the goblins

here.

*In a rather sad twist, in Tolkien's later life he especially disliked MacDonald, saying "re-reading G. M. critically filled me with distaste". (Quote pulled from an excellent article

here.)

*If this subject interests you I heartily recommend John Rateliff's

History of the Hobbit, Corey Olsen's

Exploring J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit, and Douglas Anderson's

Annotated Hobbit.